✅ PLTR Buy Signals - A dive inside my playbook

The best investors "lose little when wrong, gain much when right", how can we imitate this?

Editor: Emanuele’s Notepad

The updated article can be found on Seeking Alpha (link)

When to buy? Clues from simplicity

I want this company in my portfolio. Now comes the question “When to buy?”.

Despite there is not a definitive answer to the $1trn question, I believe some clues could help us intuitively see if we are moving odds in our favour.

These clues led my decision to recently double down Palantir at $7 and will drive my decision if its price gets even lower.

This article could be considered my playbook to intuitively assess where Palantir valuation stands, without the need for complicated DCFs, which often fail.

I believe in the power of simplicity.

The job of a good investor is to spot asymmetries with relatively little downside compared with the upside. By protecting the downside, the investor can benefit from the full potential of the upside. The best investors are those who can play the convexity game “lose little when wrong, gain much when right”. Value investors call the degree of convexity “margin of safety”, but in reality is the intrinsic characteristic of any sound investment in whatever asset class.

The lower the price we pay, the more convexity we get.

According to my experience, 2 dimensions could help to maximise the margin of safety:

Company vs. value (price of what you pay vs. what you get);

Company vs. all (relative value vs. peers vs. market).

The first is by far the most important because it incorporates the essence of investing: we make a good investment only if we pay less than the value we receive.

Otherwise, we are speculating someone pays more for the same asset, but that is not the game I am willing to play.

In this article, I will explore this dimension.

Price is what you pay. Value is what you get

When we buy a company we are buying a financial tool that represents the right on flows generated by the company. The value we get is therefore a combination of cash flows and the expectation of the growth on coming flows.

Comparing the price we pay to the flows generated by the company provides a “multiple”.

Sustainability and growth? High multiple;

Instability and no-growth? Low multiple.

Under this framework, the performance we can expect from a stock is derived by:

Performance = Multiple Expansion (or Contraction) + Business Growth

In other words, if we buy Palantir at an $8 price (P/FCF 25x) the performance we receive will be a combination of the expansion of the multiple and the growth in FCF:

Multiple stays at 25x P/FCF, business grows 30%: stock grows 30%;

Business grows 30%, Price stays at $8: multiple contracts to 17x P/FCF.

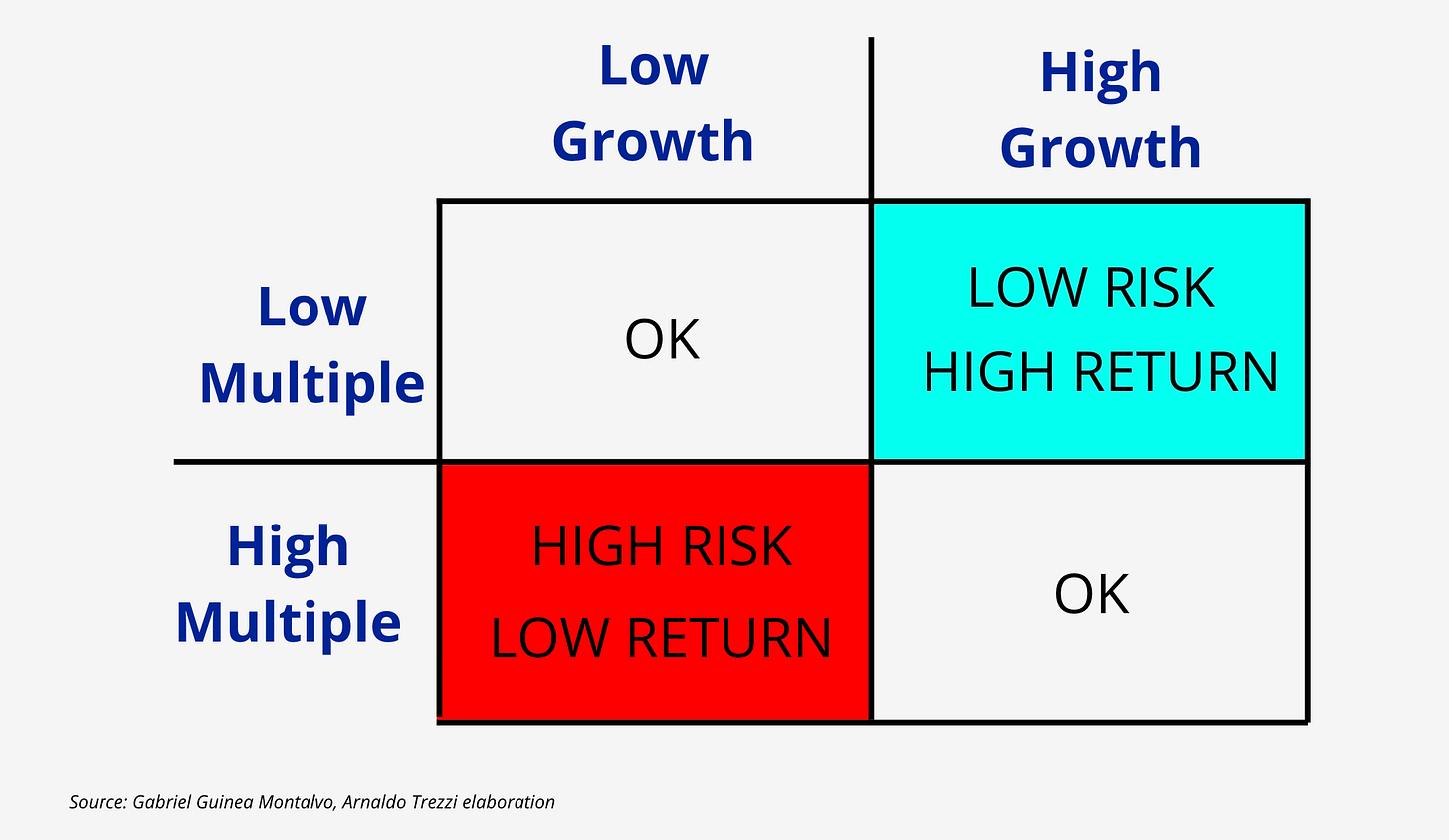

The combination of multiple and growth determines different risk profiles. The combination of low multiple associated with high growth is the dream case for any investor because it offers the best risk/reward outcomes.

More for less: understanding the multiple

Buying lower multiple increases the chances of good performance. This is not only because we “get more for less”, but also because we become more exposed to a potential revaluation of the multiple while being more protected from the downside of multiple contractions.

What multiple should I consider? The choice of the multiple is mainly driven by the stage the company is at. We want a stable metric to intuitively assess where we are in terms of valuation.

EV/Sales multiple is often the only metric we can use for early stage companies because there are no cash flows generated after the Operating Expenses are covered.

EV = Market Cap - Net Cash

The harsh truth is that if we need to value a company on EV/Sales we are in the highly speculative zone where it is very easy to overpay for companies with negative FCF.

As a proxy, I consider 15x EV/Sales the most that I am willing to pay and should be associated with strong growth and potential margins. When I bought Palantir at $10 at DPO, it had 15x EV/Sales combined with a 50% Revenues growth and negative Free Cash Flow.

Focusing on companies already producing FCF with a steady Margin reduces the probability of making mistakes.

What’s the right price for growth and FCF?

As a general principle, the multiple is “cheap” when we buy large growth or strong resilience (or both) for a little multiple.

Dealing with companies with FCF is safer and easier because we could use a simple yet powerful model.

Fortunately, PLTR now produces FCF with pretty stable margins (~30%) and therefore is suitable for it. The recent contraction is probably due to strong client acquisition as highlighted in the previous article.

By comparing the EV/FCF multiple to the growth we adapt the Price-Earnings-to-Growth (PEG). This allows us to judge:

not appealing: EV/FCF > growth %;

fair: EV/FCF = growth %;

appealing: EV/FCF < growth %;

very appealing: EV/FCF is 1/2 of growth %.

This simple valuation tool is powerful because it incorporates the idea that growth is extremely valuable to investors.

If we can buy “much growth for less” we got a good deal.

Conversely, paying a high multiple for companies not growing much could leave investors exposed to little or no growth and multiple contractions. These lead to catastrophic effects on the performance (ouch!).

Let’s take Palantir as an example. I consider Palantir a 30%-grower, therefore according to the model, I am:

“not ok” to pay much more than 30x EV/FCF (price > growth)

“ok” to pay 30x EV/FCF (price = growth);

“happy” to pay a multiple 25x (price < growth);

“excited” to pay 15x (price = 1/2 growth).

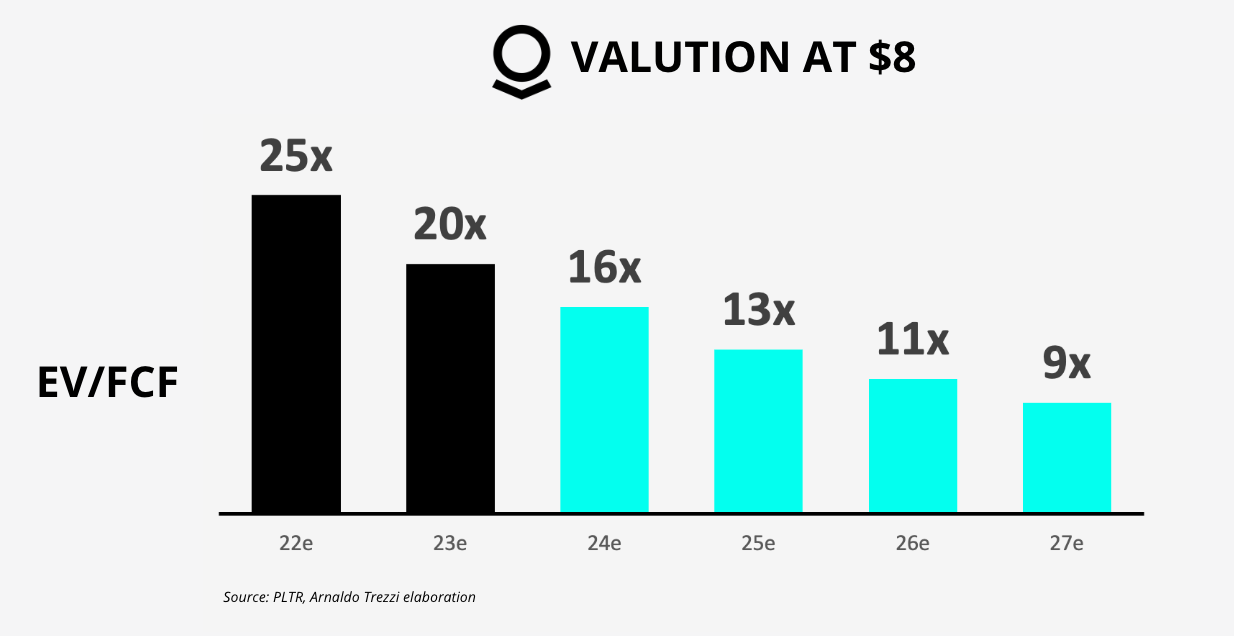

I use this table to easily assess the multiples at different prices:

These multiples include the effect of SBC in terms of the increased number of shares.

It is all about growth. What growth?

What is cheap for one company is not cheap for another. It is all a matter of growth and its resilience.

“How can I choose the “right growth”? Here is where the understanding of the business comes into play.

With companies at a mature phase, Return on Equity (ROE) and Return on Invested Capital (ROIC) offer clues to sustainable growth. With companies at an early stage like Palantir, we need to do a lot of homework in understanding the business to become confident that the business can grow at a certain rate.

The “right” growth rate depends on the business structure and specific strengths. Understanding what drives the durability of the growth is far more important than understanding the next quarter's growth.

These considerations display that 30% is a reasonable “sustainable growth rate” for Palantir’s foreseeable future:

~38% Revenues avg. yearly growth in the last three years;

+30% yearly Guidance until ‘25;

~32% yearly growth of existing clients (132% avg. Net Dollar Retention).

Larger B2B SaaS peers like $NOW (PLTR vs NOW article) and $CRM grew more than 20% for more than a decade. This supports the idea that, with the right execution, Palantir could sustain that 30% growth.

Don’t worry, I’ll pay you back “later”

To understand the importance of growth consider the 2 cases of buying an entire business at 20x EV/FCF:

no growth: it would take us 20 years to return on our investment;

20% growth: it would take us 9 years to return on our investment.

The 20% growth makes us “save” 11 years of investment.

FCF multiple tells us “how many years at 0% growth do I need to fully return on my investment”. A multiple of 20x means that it takes 20 years at fixed FCF rate to fully receive a return on my investment.

Growth accelerates that process. Observing how growth impacts the multiple we pay could be helpful to assess if we risk overpaying for it.

When is the multiple too cheap to ignore?

To address this question, let’s see how a 30% growth affects Palantir's valuation at different purchase prices.

Case 1:

At $8 we purchase Palantir at 25x EV/FCF but if the price stayed at $8 for 3 year the multiple would decrease to 16x due to stronger FCF.

This would be intuitively “too cheap to ignore” for a company growing 30% with 30% FCF Margin.

Case 2

Conversely, if we pay $20, so 71x EV/FCF, it takes many years before the multiple becomes “attractive”.

Note, it takes 6 years of 30% growth to get to the starting point of $8.

Case 3

If we consider the $5 case, underlined by many bears, Palantir would have 14x EV/FCF.

If we invert the 14x multiple, giving 7% return in the first year, this would equal the avg. market return of the S&P500. However, the table below shows that this multiple is more likely associated with a Utility company rather than a potential Alpha company.

A 14x multiple is generally associated with sub-average companies or with little expectations of growth, for instance IBM or GE.

With 30% growth at a fixed 14x FCF Multiple, one could 3x the S&P500.

From here, the convexity would be remarkable:

Downside case: even if growth slows to 20%, the multiple contraction would have little effect;

Upside case: if growth accelerates and the multiple expands, returns could be explosive;

With 50% FCF growth and the FCF multiple expanding from 14x to 50x due to investors sentiment, a $5 shareholder could see ~250% return.

The risk of overpaying or misjudging growth could be detrimental

Our duty as investors:

do not overpay;

study the business development (products, TAM, competitors);

understand the structural growth;

do no get lost in precise DCFs or quarterly data.

Understanding the business at a deep level provides information to better assess the growth trajectory and its durability.

Paying low multiples without paying enough attention to the durability of the growth could bring detrimental results.

This is the mistake I made with BABA last year. I bought at 20x Price/FCF because the business was growing +20%, however I underestimated the government crackdown and the overall slowdown of the Chinese economy. These reduced growth and the multiple accordingly - aka double hit.

BABA needs to reconstruct its Income Statement from 0 each year, therefore it is highly affected by the macro environment. Conversely, Palantir has a business structure with contractual recurring Revenues and client expansion. This means stable Revenues and subsequently stable FCF.

Conclusion: a simple principle

If the growth trajectory is untouched, our performance will become a matter of the price we pay. The lower the price we pay, the more convexity we get.

We can’t predict how our stocks move, but by studying the business deeply we can:

have a reasonable expectation of the sustainable growth rate;

pay a low multiple when Mr Market offers us the opportunity.

Key principles:

Underpaying allows for a margin of safety in the case of slower growth. Overpaying can be detrimental for returns.

Yours,

Arny

Join me on Twitter: @arny_trezzi

View expresses are my own. Do not represent Financial Advice.

I own PLTR 0.00%↑ stocks.

https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/01972243.2022.2100851 (Do you have this info. Important.)

Would you be willing to break down how you are calculating FCF? Because this looks quite inaccurate.